V8 Exploitation Series - Part 2

High-Level Architecture

Introduction

There is a lot of information to cover to understand this code base, so we’ll begin by looking at some of the major components so that the terminology in future posts and other articles will make sense. I am going to rely on a lot of references to introduce this material because plenty of high-level descriptions of V8’s components already do a much better job than I could in such a short post.

V8 in Chromium

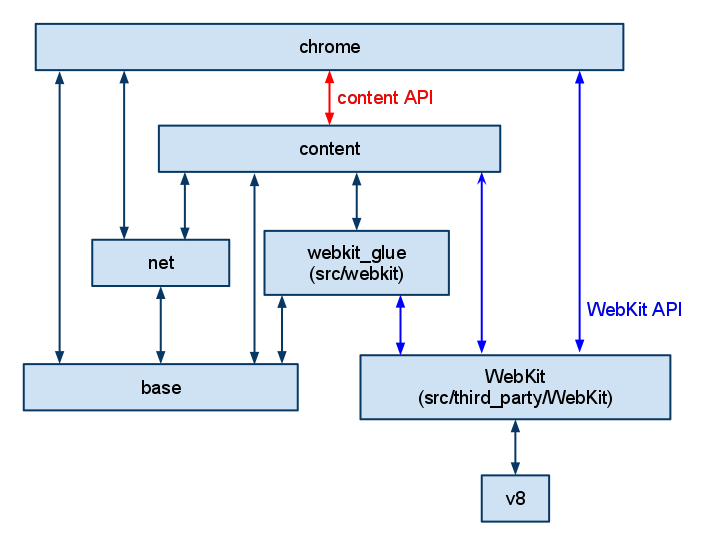

V8 itself is a relatively small piece within the Chromium browser. In fact, it is a completely separate code base that can be embedded within other projects (like NodeJS!). It is important to understand the layout here because we will talk a lot about V8 exploitation, but V8 is usually sandboxed within another process(es). V8 bugs must be chained with additional exploits to reach full blown code execution on most systems. For our purposes, we will be happy to gain unrestricted code execution within V8’s process. For example, this is a high-level look at Chrome that shows how V8 is situated within multiple layers of components.

Credit: https://www.chromium.org/developers/how-tos/getting-around-the-chrome-source-code/Content.png

The cool thing about V8 being so modular is that we do not have to dig deep into any other code bases to understand it. While looking through Chromium source code could paint a better picture for certain design choices, it is largely unnecessary.

V8’s Components

Now we’ll explore some of the most important parts of V8. You can find all of the code here or at the GitHub mirror. In my next post I’ll go in-depth as to how these components are written in C++, but for now let’s just get an understanding of what they do.

To understand the way V8 is segmented, you have to look at how modern web browsers run JavaScript. Although it is an interpreted language, JS engines often compile this code into architecture-specific machine code in a process known as Just-in-Time (JIT) compilation. Normally, an interpreted script will be converted into bytecode, which can be run architecture-independent. However, this code runs very slowly as all of the instructions need to be transformed from an intermediate language into the specific instructions supported by the current CPU. Alternatively, compiled code is very fast, but it requires some up-front cost of converting the source into an executable. The idea for JS engines is to use JIT to get the best of both worlds. They use an interpreter to start running JavaScript immediately; however, if the engine detects that some code is being run often then it will compile that section of code with several optimizations to increase performance. The way that this whole process works in V8 is best explained by Benedikt Meurer in his post.

Ignition

Ignition is V8’s interpreter. Many exploits focus on JIT code and the mistakes made during the compilation process. However, the compiled code relies on what is produced by the interpreter! While fewer security-related bugs have been found here, there are still some, as pointed out by Dimitri Fourny and Moritz Jodeit. To understand this component, we recommend briefly looking over this in-depth document from Google and reading this good, quick explanation of how V8 generates bytecode by Franziska Hinkelmann.

The key takeaway is that Ignition is responsible for generating bytecode from JavaScript first. Next, we’ll talk about when other components take over.

Turbofan

Turbofan is V8’s sole JavaScript compiler, even though some resources may show references to Crankshaft (replaced in 2017 :’( ). Other engines also have various levels of optimization that are carried out by different compilers, but this is not the case for V8. Turbofan kicks in when V8 notices that a particular function is “hot” (meaning that the code has been executed a certain number of times). Once the function is compiled, it will redirect control flow to the JIT code on future calls to that function.

Most V8 exploits focus on this component, and as a consequence we will too. Some aspects to understand here will be the optimization pipeline, variable typing, and memory safety checks. There’s a great presentation (slides) for basic understanding. This article by Jeremy Fetiveau is a really awesome introduction from an exploitation perspective (note that it goes much more in-depth than we have so far).

The important part to understand about Turbofan is that it has a tough job. JavaScript was not originally meant to be compiled. It is weakly typed and allows for an insane amount of flexibility between types, and the ECMAScript standard does not always seem logical (to put it nicely). This difficulty is what causes many JS engines, not just V8, to be buggy. In our analysis of past exploits we’ll see that several vulnerabilities come from a divergence in a reasonable assumption being made about how JavaScript should behave vs. how it actually behaves.

Liftoff

Liftoff is the component that creates machine code from WebAssembly. It is able to compile WebAssembly very quickly; however, it does not produce optimized code. It actually passes its output to Turbofan immediately for optimization (as opposed to Ignition which waits for code to be run a certain number of times first). This component is updated quite frequently, and since it is relatively new, there are more and more bugs being found in it. As WebAssembly becomes more popular, there may be more opportunities for security research into this piece of V8.

Torque and the CodeStubAssembler (CSA)

To get even better performance, V8 comes with pre-compiled code for built-in functions (the functions defined by the ECMAScript standard). These used to be written in the CSA, which was introduced in 2017. However, the process of hand-writing these assembly functions lead to several bugs, prompting the introduction of Torque a year later. Essentially, Torque makes it easier to write efficient code for built-in functions across the various architectures supported by V8.

Another great post was actually published while I was writing this section. It does a fantastic job summarizing not just an exploit involving Torque, but many other concepts I have talked about already.

Conclusion

Now we have covered some of the major components listed in the V8 docs with a high-level summary of each. From here, we will mostly focus on Turbofan, taking a slower approach than most of the existing vulnerability research in an attempt to get a very low-level understanding. Much later we will look back at Ignition, Liftoff, and Torque.

References

https://www.chromium.org/developers/how-tos/getting-around-the-chrome-source-code/